Whether it is called a national embarrassment, systemic failure, or impending pandemic, the H5N1 outbreak in the US has been widely met…with not a lot.1 In this postpandemic world—where increasingly common mpox and viral hemorrhagic fever outbreaks, surging influenza cases, and low vaccination rates are met with growing partisanship and a dwindling health response infrastructure—the fear of H5N1 is fundamentally shifting from nervousness to stern realism. Each week brings reports of new dairy farms impacted and human cases, but where are we in this outbreak that began nearly a year ago?

A Bumpier Road Ahead

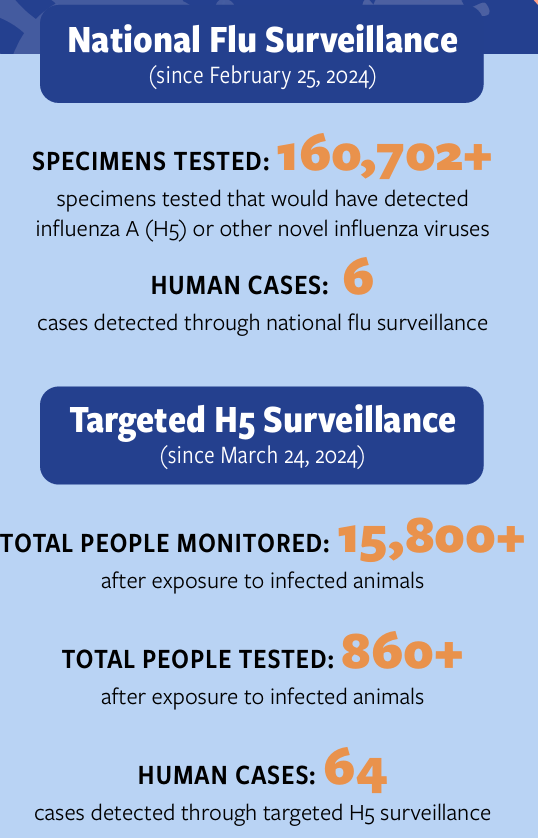

Response to H5N1 (avian influenza) has been lackluster since early February 2024, when it was detected in wild birds and dairy cows. As of March 18, 2025, there have been 70 human cases (including 1 death), 989 dairy herds affected across 16 states, more than 162 million poultry affected, and 12,064 wild birds with H5N1 detected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 The road to success in combating this outbreak is likely to get more complex as newly appointed Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr comes into his role, with leadership at CDC still awaiting placement and a less-than-ideal track record with data-driven decisions, an affinity for conspiracy theories, and a consistent push against vaccination.3 Although the CDC’s sluggish testing and reporting have been widely cited as a frustrating example of slowed response, there have been 2 recent hits to the national response that will further erode not only capacity and capabilities but also public trust. First are the recent cuts to critical staff (10,000, and with buyouts, 20,000) at the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, the CDC, and the National Institutes of Health, among others, which followed a second impacting event —the CDC removing data from its website to meet executive orders from the White House.4 A reduction in workforce, mass confusion, data deserts, withdrawal from the World Health Organization,5 and a halt on most communication from the CDC have left a significant gap in response—it is not just that we are building the plane as we fly it; we are also flying blind and through a storm.6 The reality is that although we might want to remove politics and partisanship from H5N1, we cannot, as governance and politics have always been intrinsically part of public health. Regardless of political ideology, we can all find commonality in acknowledging that the current situation is not conducive to improving the growing outbreak and missteps, such as information asymmetry and testing gaps, that occurred during the Biden administration.

Biosurveillance and Vaccination

From the beginning, the US has been on the back foot regarding surveillance for H5N1, which means it is vital that widespread efforts are made to increase testing. From additional wastewater surveillance sites to testing in higher-risk workers and economic protections for farmers/workers, there are steps we can take now to improve our stance in this outbreak.7

New human cases have recently included a hospitalized woman from Wyoming, but we have also seen H5N1 spill from one species to another. The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service within the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported the following on February 13, 2025: “Confirmed by whole genome sequence a detection of highly pathogenic avian influenza [HPAI] H5N1 clade 2344b, genotype D11 in dairy cattle in Arizona.” Furthermore, the agency shared in the announcement, “The detection of this virus genotype in dairy cattle is not unexpected because genotype D11 represents the predominant genotype in the North American flyways this past fall and winter and has been identified in wild birds, mammals, and spillovers into domestic poultry. Whole genome sequencing indicates that this detection is a separate wild-bird introduction of HPAI to dairy cattle, now the third identified spillover event into dairy cattle. This finding may indicate an increased risk of HPAI introduction into dairies through wild bird exposure.”8

With this news, it comes as a welcome relief that the USDA has conditionally approved a poultry vaccination to protect flocks. However, Science’s Jon Cohen noted, “Even with the conditional approval, USDA must still approve its use before farmers can start to administer the vaccine because special regulations apply to H5N1 and other so-called [HPAI] viruses.”9 Hopefully, this approval indicates a shift in response that might help reduce potential spillover, but we are not out of the woods yet.

Surging Influenza and a Path Forward

With soaring egg prices on many people’s minds, there is another significant fear behind this urgent need for containment: viral reassortment. With surging influenza cases this 2024-2025 season and no signs that H5N1 is letting up anytime soon, the concern is that a novel reassortment might occur in which H5N1 would gain the capacity to spread more efficiently between humans or cause more severe disease. Not surprisingly, this is where the importance of data—both surveillance and reporting—comes into play. A new Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the CDC highlights the reality of limited surveillance and human cases occurring without recognition. Per the CDC, despite no reported influenza-like symptoms, “Among 150 bovine veterinary practitioners, 3 had evidence of recent infection with HPAI A(H5) virus, including one who only practiced in 2 states [Georgia and South Carolina] with no known HPAI A(H5) virus infection in cattle and no reported human cases, this practitioner reported no exposures to animals with known or suspected HPAI A(H5) virus infections. These findings suggest that there might be HPAI A(H5) virus–infected dairy cattle in states where infection in dairy cattle has not yet been identified, highlighting the importance of rapid identification of infected dairy cattle through herd and bulk milk testing.”10

Prevention and identification of human cases to ensure isolation and avoid any potential further transmission is becoming increasingly critical; this relies on a robust biosurveillance network, where data collection and reporting are accessible, and communication and public health resources flow freely.11 As it stands, we can expect 2 things: changes to continue as the Trump administration settles in, and this outbreak to worsen if we do not make immediate changes.